Contemporary drawing depicts European settlers trading with American Indians.

European Contact and Settlement

In 1760, travel writer Andrew Burnaby crossed the Blue Ridge Mountains and beheld the Shenandoah Valley. After acquainting himself with the land and the people that inhabited it, he wrote in his travelogue:

I could not but reflect with pleasure on the situation of these people; and think if there is such a thing as happiness in life, that they enjoy it. Far from the bustle of the world, they live in the most delightful climate, and richest soil imaginable . . . in perfect liberty: they are ignorant of want, and acquainted with but few vices. Their inexperience of the elegancies of life precludes any regret that they possess not the means of enjoying them: but they possess what many princes would give half their dominions for, health, content, and tranquility of mind.

But the geography and agricultural riches of Burnaby’s musings had been home to many long before the arrival of the frontiersman that he encountered in this travels.

Native Americans had occupied the Shenandoah Valley for more than one hundred centuries before Europeans began to settle the land. By the seventeenth century, conflicts over trade and territory among the Indian nations inhabiting the Shenandoah forced them to abandon the land, leaving it seemingly deserted. One of the only indications that Indian nations had previously occupied the Valley were what came to be known as Indian “old fields”—forest areas that had been burned to facilitate travel. The apparent absence of Indian presence in the region encouraged settlers to choose this area, where the land was arable and the threat minimal.

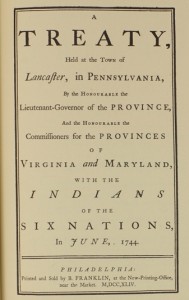

In hopes of ensuring the safely of European settlers, Governor Spotswood of Virginia signed a treaty with the Six Nations (also known as the Iroquois Nation) in 1721, wherein the Iroquois tribe consented to remain on the west side of the Blue Ridge Mountains in their conquests of southern tribes’ territories. In 1736, however, the Iroquois began to object, arguing that although they did not occupy the Shenandoah Valley they still had legal rights to the land.

Before this Iroquoian objection threatened their livelihood, Europeans had begun settling the land in the early eighteenth century. Virginia governor William Gooch established the Opequon Settlement, a land policy intended to safeguard settlers in “Old Virginia”—the land east of the Blue Ridge Mountains—from American Indians. European families owned tracts of land averaging three- to four-hundred acres that served as “buffer settlements” between Indians and the more settled European colonies of the east.

Among the families settling the Shenandoah Valley were Quakers and Mennonites, who had traveled south from Pennsylvania. The similar lifestyle of these settlers to that of the American Indians warranted a peaceful relationship: both parties lived off of and respected the land, and relations were largely amiable.

Tensions rose, however, when the Iroquois began to object over the 1721 treaty and began to claim ownership of the land now settled by almost 5,000 Europeans. In the fall of 1742, the amiable relations that settlers had enjoyed yielded to European wariness of Indian presence. War parties of Seneca (of the Iroquois Nation) and Lenape tribes traveled through the Shenandoah Valley en route to North Carolina, where they were engaged in war with the Catawba Indians. Traveling in the late fall, the need to store food for the colder months compelled one of these tribes to kill several horses and a hog, which were considered private property by the Europeans. This event, compounded by many others committed by both parties, led to increased hostility between the settlers and the Indians.

When news of the conflict reached Governor Gooch, he decreed that all Indians should be treated as a threat, and the violence only escalated. The ensuing two months witnessed many murders and betrayals, and the events of the winter of 1742 came to be considered a tragedy by settlers and Indians alike. Finally, as the Iroquois threatened to declare war on the Colony of Virginia, Governor Gooch paid the sum of 100 pounds sterling for any settled land in the Valley that they claimed. The following year, the Iroquois sold their remaining claim to the Valley for 200 pounds in gold in what came to be known as the Treaty of Lancaster.

After the skirmish with the Indians had subsided, peace was restored in the area and settlers began to migrate to the Valley in greater numbers. Winchester, at the northern end of the region, predominated over a group of smaller towns, some consisting of only a few shops and houses. Agriculture—particularly wheat, corn, oats, barley, and rye—sustained a flourishing economy, as did flour, beef, wool, and other animal goods that were brought to trade. The serene landscape of this valley just west of the Blue Ridge Mountains attracted farmers and plantation owners alike, and as the townships became better established and the population grew, larger and more prominent houses were constructed at the turn of the century. Having inherited 1,000 acres of land from his grandfather, Robert Carter Burwell was among these plantation owners, and he resolved to build a house that would establish his presence in the heart of the Shenandoah Valley. Here, the history of Long Branch begins.